Quintan Ana Wikswo

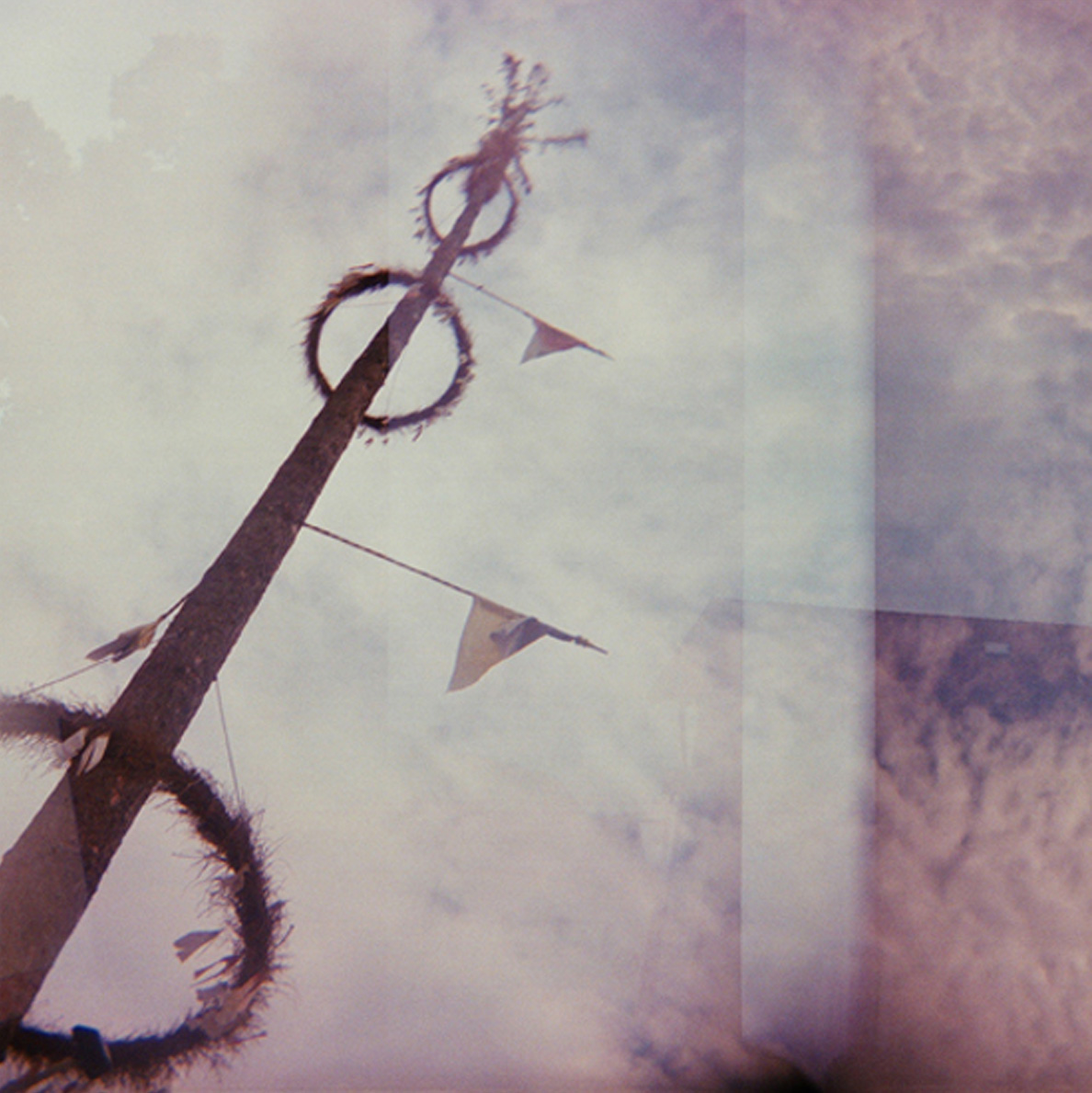

"The colors, textures, shapes and multiple layers within the photographs are all created using only the unique aberrations of the cameras’ optics, and the chemistry of the film. There is no software or computer manipulation in the images."

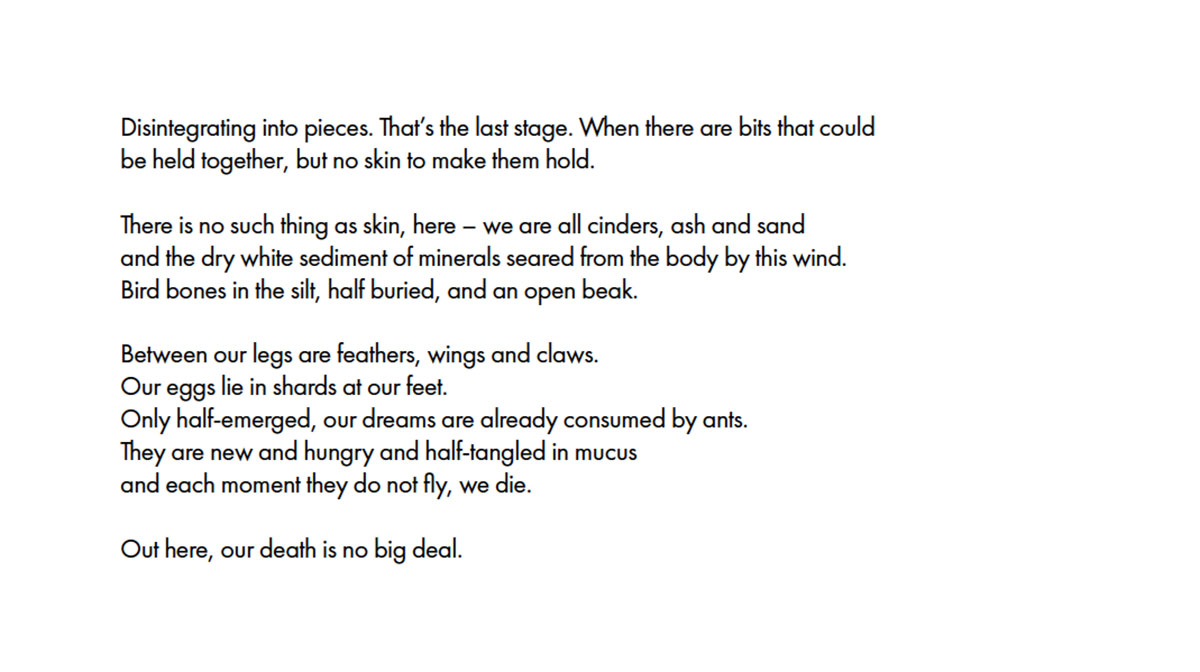

fieldwork

“FIELDWORK is an autobiographical project about my years in the femicide regions of the Southwest and US-Mexico border and Tohono O’Odham Reservation, and my time as a fieldworker setting up safe houses for sex trafficked women and children. For this project, I returned to sites where I used to work, and created a Vulture Vigilante alter ego. Wrapped in one of the mylar FEMA emergency blankets distributed in the safe houses and used by fieldworkers to protect the bodies of dumped women, the Vulture Vigilante both guards the site, exhumes the site, and harvests out the beliefs and behaviors of a human society in which the murders of women and girls are a normalized part of daily life. Her role is shamanic, for she walks between the world of the visible living and the invisible dead…yet she also walks between the versions of reality in which female lives are worthless and our violent deaths unremarkable, and a new future in which our bodies and psyches have intrinsic value. As the Vulture locates these bodies, she reveals that the bodies themselves are also hybrids – the women are being transformed from victims into vigilantes. She stands on their graves, invoking them to rise from the dead and seek retribution, justice, and social change.”

These photos were created using salvaged damaged film cameras manufactured by fascist dictatorships.

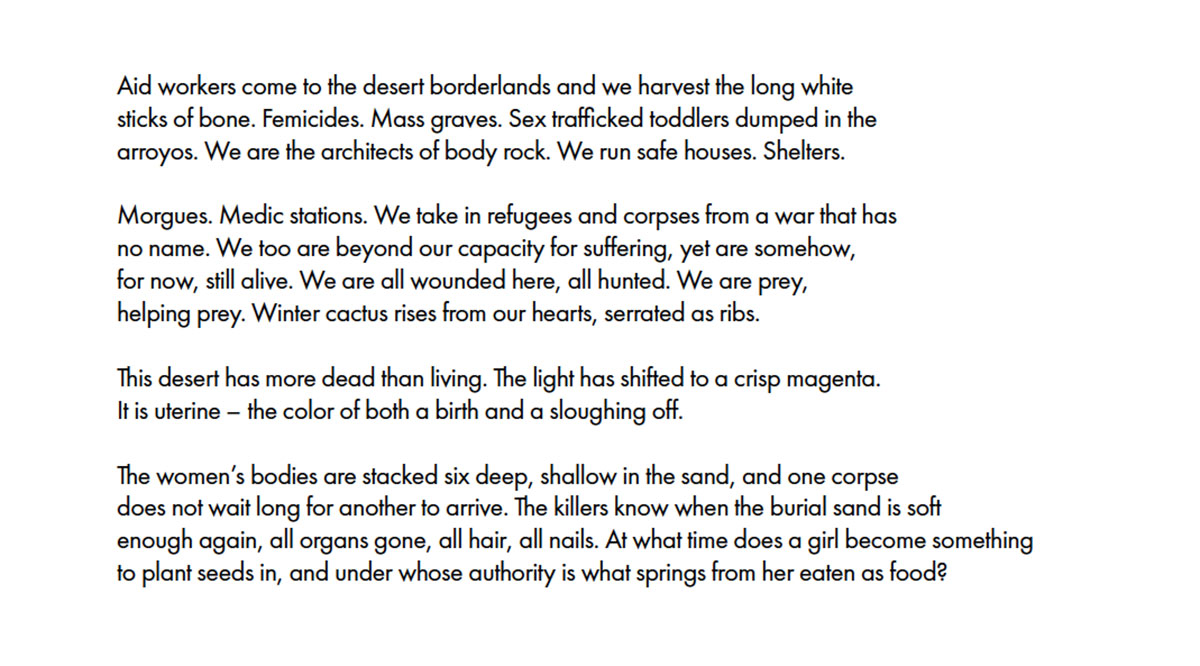

“An American woman and a German woman go on a date in Berlin. As they eat, drink, and begin to dance, they discover their mothers were both patients of a notorious Nazi gynecologist from the Charité Hospital, but under vastly different circumstances.

Part of Mercy Killing Aktion, CHARITÉ explores sites of gender-based biosocial war crimes through a constellation of works in literature, photography, film, and performance collaboration.”

THESE photographs were created in Berlin, at the sites of the Nazi Aktion T4 gynecologists’ and obstetricians’ offices in and nearby the Charite Hospital. The photos were made using salvaged 120mm film cameras manufactured by Dachau slave labor at the Agfa camera factory in Munich.

“Even cursory research made clear that the project was awkward and difficult – within a society that even today tolerates epidemic levels of domestic violence, sexual crimes against women, sex slavery within the trafficking system, and gender-based violence, how to talk about women’s experiences during the Holocaust and World War II? Why should I? Why should I take on this particular project? Was it the institutionalizing, the industrializing of rape? Was it the sensationalism of the Nazi genocidal sexual psychology? Was it simply the compulsory ritual for every Jewish artist to create a major artwork surrounding the Holocaust? These questions were preoccupying.”

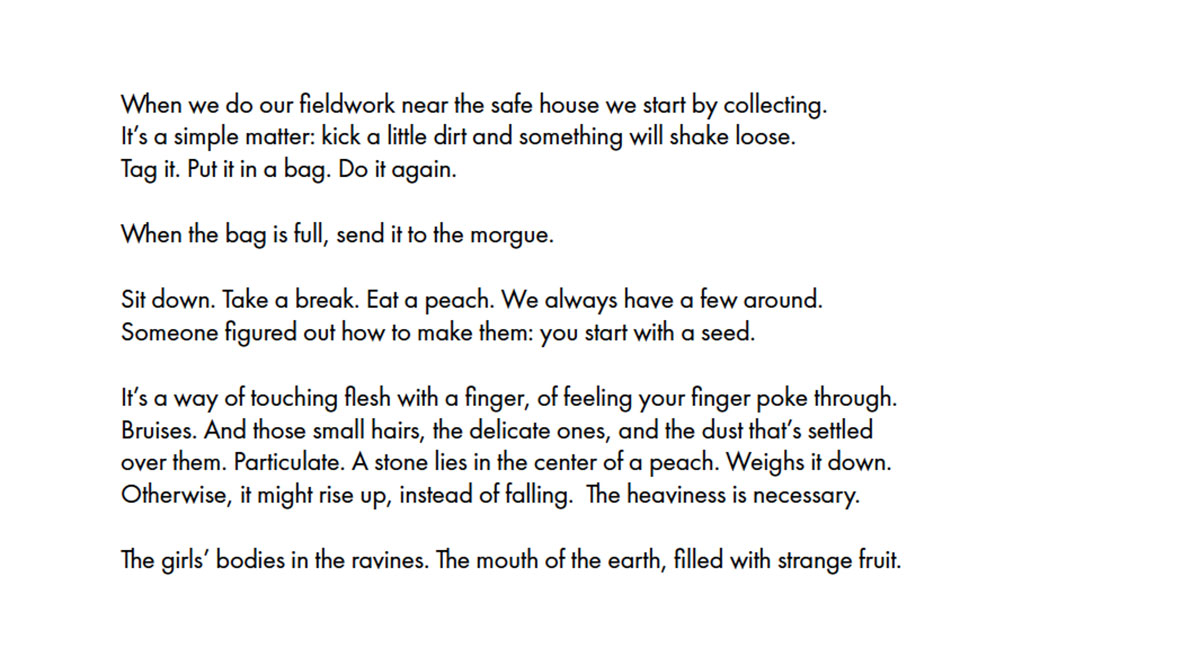

photographs were created at the site of the rape brothel at Dachau, using salvaged 120mm film cameras manufactured by Dachau slave labor at the Agfa camera factory in Munich.

“I created these pieces while working in a small Bavarian village. Every day, I walked along a narrow lane to buy bread, and passed women of the village cleaning gravestones in the churchyard. Nearby, a road sign was marked with a man’s name that I later came to recognize as that of a medical war crimes doctor. Once, on the walk back to my studio, I had an epileptic seizure and rested for some time on the bench just inside the cemetery walls. As the villagers critically assessed my situation, I began to create KLITZEKLINE URNE in my mind.”

photographs for KLITZEKLIENE URNE were created in small villages in Bavaria, using salvaged film cameras manufactured by forced labor in Nazi Germany.

“At the heart of my work are questions surrounding the construction and depiction of reality and realities – truths and histories. I am curious about how tactics of storytelling and narrative are used to create and control mythos and historicity – as weapons of hegemonic power, but also as tools of resistance and liberation. I investigate how narratives are coded into the human body, mind, and psyche through a potent matrix of sexuality and erotics; trauma, violence and militarism; and altered states of consciousness.

For several decades, I worked for human-, civil-, and gender rights organizations in the United States, Europe, Central and South America, and various North American Tribal Nations. Within this work, I focused on projects with which I had first-hand personal, direct and/or ancestral experience – I therefore stood simultaneously as witness and as instigator, as activist and victim, insider and outsider, survivor and bystander, solution and problem, rescuer and betrayer.

My job was the construction of official narrative: reporting on, crafting, and compiling oral histories, survivor testimonies, victim testimonies, white papers, government reports, law enforcement reports, social services and psychiatric evaluations, news articles, stakeholder reports, diplomatic briefs, and ghostwriting speeches and strategic communications for officials and powerbrokers on various sides of the prevailing power structures.

Today, my interdisciplinary projects investigate how states and their institutions and communities define and police the official stories of normalcy and belonging. How is narrative used to enforce control over human activity, and what are the methods of enforcement? Where – and on whose bodies – are official histories encoded over time? What are the processes for disruption and interruption of these coded stories?

How do poetics and visual abstraction hack this code, and provide a renegade underground railway for insurrection and disobedience?

My bodies of work explore and inhabit unmarked, intentionally obscured, and hidden sites where trauma has literally “taken place” – sites whose experience of atrocity have been erased from public record, and where contemporary efforts continue to actively obscure or erase the aftermath narratives. I work at these sites over a period of 5-10 years, using with salvaged military film cameras and typewriters manufactured by Fascist and authoritarian governments.

I create multi-voiced portraits of place over time, and time across place…constructing new evidence that resists erasure and interrupts the prevailing narratives. I work in literature, photography, video/film, and performance to create a single project. Each project is comprised of a constellation of independent but interconnected poems, texts, stories, essays, video installations, large-scale photographs, books, solo and collaborative performance works, and site-specific rituals and rites.

In my photographs, videos, texts, and performances, I work to dislodge these timespace situations from their habitual representations and contexts. I work with the instruments to actively interrupt conventions and disrupt narrative and visual controls. They exhibit inappropriate, intrusive, and distracting aberrations in spelling, focus, spacing, exposure, margins, characters, and framing.

Because tangible, material evidence of atrocity is typically removed from these sites, the place itself is a volatile abstraction in a constant state of destruction, construction, and deconstruction. Because the cameras and typewriters themselves are unlikely survivors of violence, they have unique capacities, wounds and histories.

My challenge is to incite new encounters and engagements with sites and stories that have been silenced. I am not interested in presenting an official story or replacing an old history with a new history. Instead, I wish to create a conversation with these disrupted voices and places to invoke a constellation of human realities that prevents communities from indulging in the worship of a single unified message.”