Nora Kelly (she/her) is an oil painter and muralist based in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She spent the year of 2017-2018 in Mexico City, Mexico, apprenticing with the muraling company Street Art Chilango and has since painted murals for businesses and private residences across North America, always with a desire to keep her services affordable and accessible to all.

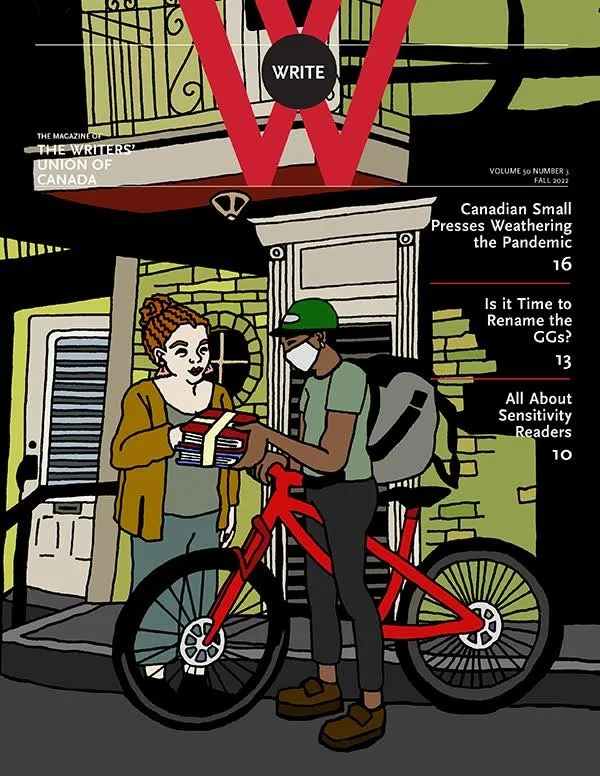

More recently, she has turned to editorial illustration and has been working for The Writer's Union of Canada, The Tyee, Capital Daily, PRISM, Vallum magazine, Raleigh Reviews and others. She lives with a dog named Squid and fronts alt country outfit the Nora Kelly Band.

Editor’s Note:

My first interview as Features Editor for BTL was an absolute pleasure. Nora Kelly is a down-to-earth artist empowered by a punk ethos and driven by an earnest desire to create art that is progressive, socially-informed, and emotionally-attuned. Her art style is surreal yet grounded. Whether interrogating the complex intimacy formed during COVID-era lockdown or reckoning with record-breaking climate catastrophe, Nora Kelly’s art doesn’t flinch. The same can be said of her witty lyricism and melodic vocals as front woman of Y’allternative rock ensemble the Nora Kelly Band. Make sure to check out their debut album Rodeo Clown when you finish reading. You won’t regret it!

— Evan C. Loving

How do you describe your style as an artist?

Nora: As a musician, I'm a self-taught guitarist and come from a punk background. Now I'm making alternative rock/country-ish music. But the punk ethos is very obvious, I would say, if you listen to the music. There’s a sense of humor, a bit of grit. I also bring a ‘let's just get it done’ energy. I'm not gonna spin my tires in the mud. Not trying to be a perfectionist, really. I like to keep the momentum moving forward. I think that is also true in my art. For example, my oil paintings, are often big blocks of color and once it's mapped out I'm filling them in and it’s so satisfying. I don't have to take two weeks looking at the canvas like ‘oh the lighting! It’s just not quite right here’ you know?

I have a lot of appreciation for the other side, especially in music, like I have some incredible players in my band who are much more thoughtful and curate the specific. Thinking about that helps to rein me in a little bit because I'm sort of a force of ‘we gotta do it!’ But I do feel that painting or illustrating help me to take a deep breath, to be more patient. Otherwise, I keep myself super busy until I burn out at the end of the day. So by its nature, visual art asks me to sit in comfortable silence, to be still and I think I need that to be like a normal person.

Who are some of the artists that inspire you?

Nora: These days I really love some of the Mexican surrealist painters from the 70s. Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varos, and Leonora Carrington—I think she just lived in Mexico but she's British. I wouldn’t say that I saw their work and based my style on theirs, rather my illustrations and paintings kind of touch home with the style they created. I'm also inspired by graphic novels. I really love the high-contrast graphic black-and-white style of Black Hole by Charles Burns. I go back to the tarot a lot too, the Rider-Waite edition.

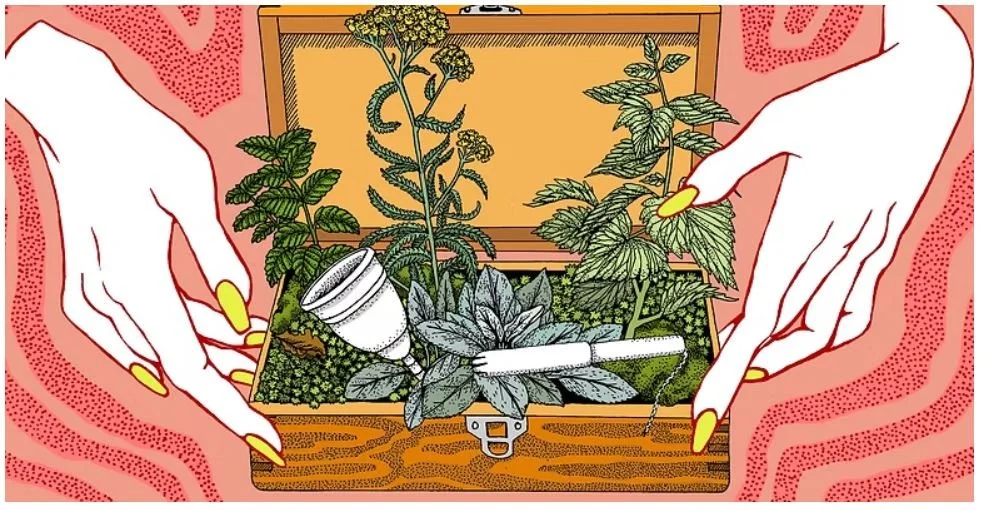

You've put language to some of my emotional reactions to your work. The way the lines move and colors blend in your oil paintings invoke surrealism. The texture of your illustrations, particularly for The Narwhal, showcase that graphic novel flair; they’re so eye-catching. The illustration of the magical box is one I kept coming back to. Tell me about that piece.

Nora: I illustrated that piece for an article about a hiker who got her period on the first day of a four-day solo hike. She hadn’t packed tampons or anything and considered turning back around, but ended up using [merino wool as a menstrual pad]. The author lays out some statistics showing hiking [in Canada] is much more common with men than women and with white people and not really other demographics. The article was partially an exposé on that. She also researched indigenous practices around menstruation and a lot of women used moss which is hyper absorbent. They learned from looking at how birds build their nests.

I wanted witchy, high-level feminine-coded energy for that illustration. There are the witchy, hyper-feminine hands, this magic box with different plants that indigenous people use like nettle and mullein inside, as well as the diva cup and the tampon—things that are commonly used today.

The connection and contrast between the ancient, natural ways and the modern methods for living with divine femininity in the day to day is powerful. When did you begin painting and illustrating? Was visual art an important part of your childhood?

Ever since I can remember I was a drawer, a doodler who would get in trouble a lot in school for not focusing. I was focused on drawing until I was putting in my application for university. But even before I went to Concordia, I had this dream of becoming a muralist specifically. Before I went to university, I decided to study studio arts with a minor in urban studies. As an 18 year old, I thought that the combination of those two things would set me up perfectly for becoming a muralist. When I was actually in university, I realized that urban studies is more the history of urban planning, but I really enjoyed it. So, you know, no regrets. Even before I started art school, I liked the idea of doing public art and stepping outside of the gallery space. I think that's still relatively true to my practice, even though it's kind of taken its own form.

What drew you to the more public spaces where murals flourish as opposed to the more traditional gallery scene?

Since I was a child, there was a kind of an energy at the local art gallery—you’re supposed to be quiet, you can’t touch anything. You see certain age groups and types of people that [gravitate] to art galleries. In Vancouver, where I’m from, there's one called the Vancouver Art Gallery and as much as I enjoyed going there, in my heart and what I wanted my practice to be, I didn't feel comfortable in that space.

I feel you. In the parts of the US that I’ve lived, art galleries tend to attract older, wealthier, and whiter crowds. There’s a level of esteem, of prestige that’s imbibed in these spaces you know?

It's highly competitive to get a spot and there isn't that much room even for young artists to be seen in an art gallery. So I had this reckoning of, if I want to go in this direction with my life and really take this seriously, does that mean I need to end up competing to enter this mythical space? Meanwhile, I saw these fun murals around town that were making public spaces feel more community-oriented, when done right. There's a lot of politics even around muraling that I learned in university.

How did university inform your understanding of ‘the politics of murals?’

In that period [after studying muraling] in Mexico City, I took classes on Latin American urban development and was exposed to ‘white savior muraling complex.’ It’s when white people go to other countries to paint these murals but don’t know the neighborhood, its culture, or needs; they arrive, their mural pops up, they leave, and then the neighborhood becomes more expensive, for example.

Tell me about painting “La Bibliothèque est Ouvert (The Library is Open)?”

That one has some significance. Yeah, I was hired by a Queer community organization to do a live mural painting for the 2023 Montreal Arts Festival. I was honored but not necessarily the right part—well, I'm not queer. So how do I approach this?

In a way, you were grappling with the politics of self-expression. Representation absolutely matters and it does raise the question: well, what do you do when a queer organization reaches out to you, a non-queer person for a gig? How do you make art that honors the community that you're in conversation with?

Yeah, exactly. So for the festival I decided to paint a mural of Montreal-based drag queen Barbada to help people to get to know her and her community work. The organizers were able to contact her for approval of the photo reference and my drafts well before the festival. I was intentional about not inserting myself too much; my goal was to celebrate someone who’s doing good in the community. The mural is a part of the conversation about Drag Queens reading to kids, which is polarizing in Canada as well as the US. She has received a lot of backlash for her work and identity, but continues to fight the fight and she's very beloved in the community.

“Rich White Man”

There’s another mural of yours that stood out to me, “The Cosmic Handshake.” What’s the story there?

When I was in Mexico City, I worked for a muraling company called Street Art Chilango. Essentially, this company does guerrilla advertising for clients like Ray-Bans or Vans. They’ll paint a big mural for a client and include a hashtag instead of the brand name. If you look up the hashtag, you'll see that it's Vans. As their intern I learned about spray techniques and met cool artists, but after the six months was finished, I told them that I wanted to go out on my own.

I stayed in Mexico City for another six months and literally went door to door, talking to random people. One day in a market, I met this guy, Elias, who was drumming there. We started talking and he told me he was the editor for the New York Times Mexico, which was kind of this new initiative. I said ‘I'm a muralist.’ We became friends, I checked out to their office, and the vibe was kind of punk rock—very different from the advertisement job. So I said ‘yeah, I would do a mural here for you guys if you want.’ It happened very naturally.

The blending of the natural, supernatural, and alien evokes an otherworldly feel. How’d you settle on that vibe?

Elias told me there’s one saying about Mexico that Mexicans say: Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States.

[Erupts with laughter]

We came up with the concept together. We felt this really rich spiritual energy in the city, but also the uncertainty of corruption. God and the Devil are shaking hands with their fingers crossed behind their backs, so it implies that whatever deal they made it's not going through. The tropical plants reflect Mexico’s perfect climate, like everything grows there. And the stars kind of hold the cosmic and natural worlds together.

There are definitely layers to the piece: the spiritual and political are in conversation with an the juxtaposition of natural scene against that void of empty space. Yeah, there's a lot of scope in there.

Given how dire conditions are for migrants in the US, I have to ask: what’s the story behind “A Migrant’s Nightmare?”

Yeah. [Migrant justice] is more relevant now than ever, really. That illustration accompanies an article by Amy Romer of the same name. She interviews Sudanese refugee Salim Elhadi [a pseudonym], about his traumatic experience being unlawfully detained at an Istanbul Airport for five months while seeking asylum in Cuba. With assistance from his sister, lawyer, and a family friend, Salim learned Gözen security, employed by Turkish airlines, were under orders from the US to “not let people who look like migrants reach American destinations.” There’s a lot more to his story and the article is absolutely worth the read.

How has the climate crisis and environmental concern influenced your artwork?

As an editorial illustrator creating illustrations for newspapers and magazines, I can't really ignore the environmental issue at large—especially in Canada.

Totally, the nation has been hit by some awful wildfires in recent years.

Yeah, and we're a natural resource-based country. We have so much water, lumber, and oil, so there's a lot of pressure on our government to extract and chop down. There’s a huge portion of the population, especially in our generation and younger, who are very concerned about environmental issues and very against sucking the country dry of everything that it has, so there's always something in the news about it. As an editorial illustrator that I get asked a lot to do environmental stuff to compliment pieces by investigative journalists about anonymous whistleblowers or exposes on companies failing to do their due diligence or leaking waste in the environment.

tell me about the “Entangled” series and what it means to you:

Before lockdown, I was muraling more and all of a sudden I had to pivot to being indoors. I thought how cool would it be to create a series of paintings that nobody saw until we get out of this. The series was very much inspired by my COVID lockdown experiences: moving in with a boyfriend and his roommates at the time; breaking up; living back with my old roommates; getting sick. There’s a fine line between leaning on or needing someone for support, and also feeling kind of strangled, like they’re driving you crazy.

Well said. Of the series, “Entangled 2” is my favorite. How you blur the boundary between tender affection and smothering closeness …

I tried to create these figures that are both caressing and holding each other but contorting their bodies at weird angles, so obviously too close. As the series continued, I included more structures, these open concept, kind of sparse and small homes that the characters are in. For me, that's one thing that my generation reckons with that some of our parents didn't. It's common to live in these small spaces with roommates or your partner, and it’s unfathomable to actually own a home. What is that doing for us socially?

For many of us that means having smaller dreams than the generation above us. In “Stairway to Heaven,” the figure is falling down stairs and their hand is going through a small door to express this idea of falling away from the dream of a bigger home and needing to accept something smaller. But also, at least in my experience, a lot of my friends are artists and musicians choosing to live more interconnected and socially in cities to pursue different dreams, even if that means making less money. We’re trying to make the best of the situation; we have an understanding that our dreams of homeownership and room to disentangle is, in a way, transferred into creating art that is ours.

What does the FUture Hold?

Are there any projects you're working on that you're excited about?

I have a painting from the Entangled series that's going to be in a Tourism Montreal showcase in a couple months. I'm also working on a children's book called Tommy's Race by Riley Windeler. The author is a little person who wrote a story about two little people who love playing sports and compete in the Dwarf Olympics. It's really cool because a lot of kids probably will go for most of their childhood never meeting a little person, but kid’s books have this power to open their minds. That's nearing its completion, so I’m excited about that.

In terms of music, my band is putting out an album next year called So Wrong for So Long. It's gonna be pretty great. We got a big grant from the government, so it's definitely our most expensive and “bougie” album. We're working with this producer who worked with Arcade Fire and The National and some big artists that I'm a fan of; he's awesome. We'll start putting out singles in February or March, and then the album will come out in May. Who knows, maybe we'll even do a little tour down to the U.S.

Nora Kelly Band

Rodeo Clown (2023)

Album art designed by Owen Ostrowski and photographed

by Gabie Allain

You can find Nora’s full portfolio at www.norakellyart.com and follow her Instagram.

Follow Nora Kelly Band on Instagram and Bandcamp.

Blood Tree Literature would like to extend special thanks for permissions to reprint Nora’s art to the attributed publications, as well as the Southern Humanities Review, the Raleigh Review, and Capital Daily. Images can be clicked to visit their original appearances.

This interview has been edited for length and style.

!["Entangled 2 [Don’t Go]" (2021), Oil on Canvas.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ff89d79de4bb950fd9ce11/fd430044-b26b-40a7-aeb0-4f63d00e2c9d/Entangled+2.jpg)

!["Entangled 3 [Stairway to Heaven]" (2022), Oil on Canvas](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ff89d79de4bb950fd9ce11/272b003f-cf74-4512-a397-db54a4ad9d81/Entangled+3.jpg)

![Entangled 1 [Are You Listening?] (2020), Oil on Canvas](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ff89d79de4bb950fd9ce11/b6c50913-a05a-45d7-82d3-2bce9b36086a/Entangled+1.jpg)